- Homepage

- News and Features

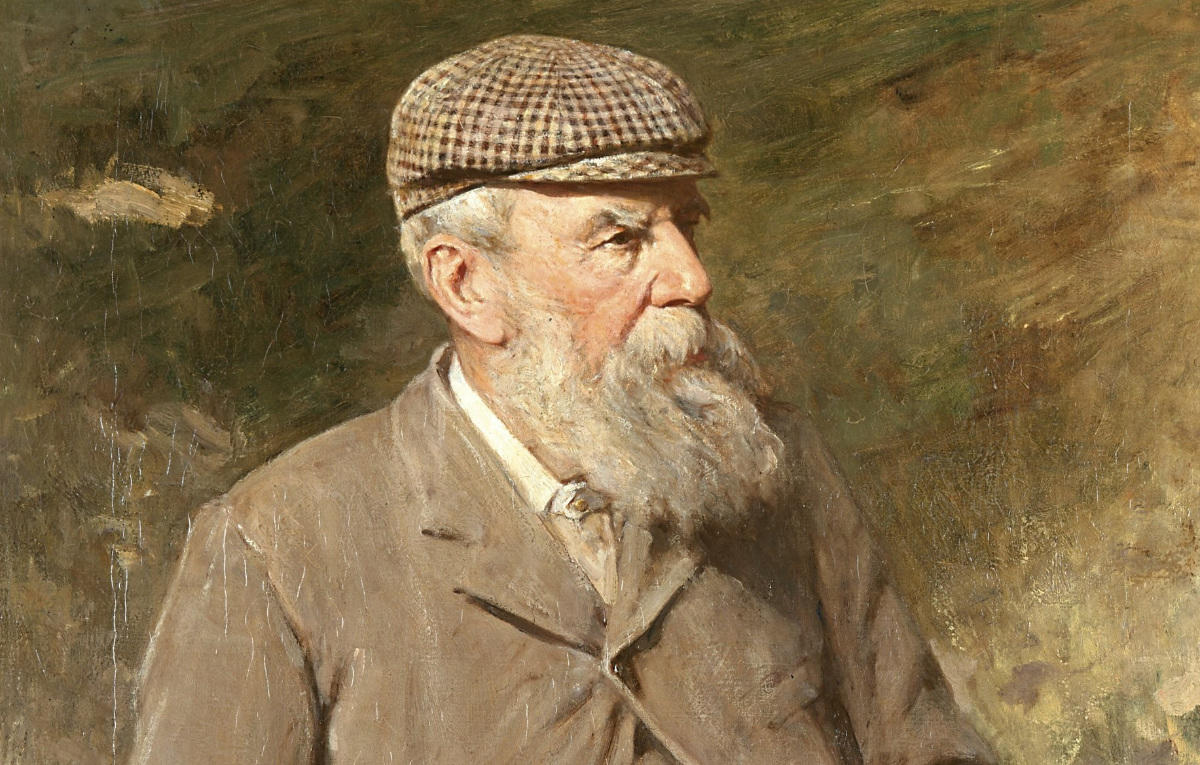

- A portrait of Old Tom Morris, the 'grandfather of greenkeeping'

A portrait of Old Tom Morris, the 'grandfather of greenkeeping'

To mark the 200th anniversary of Tom Morris' birth, BIGGA's Karl Hansell took a closer look at the life of the man who redefined golf course maintenance and has been called the 'grandfather of greenkeeping'.

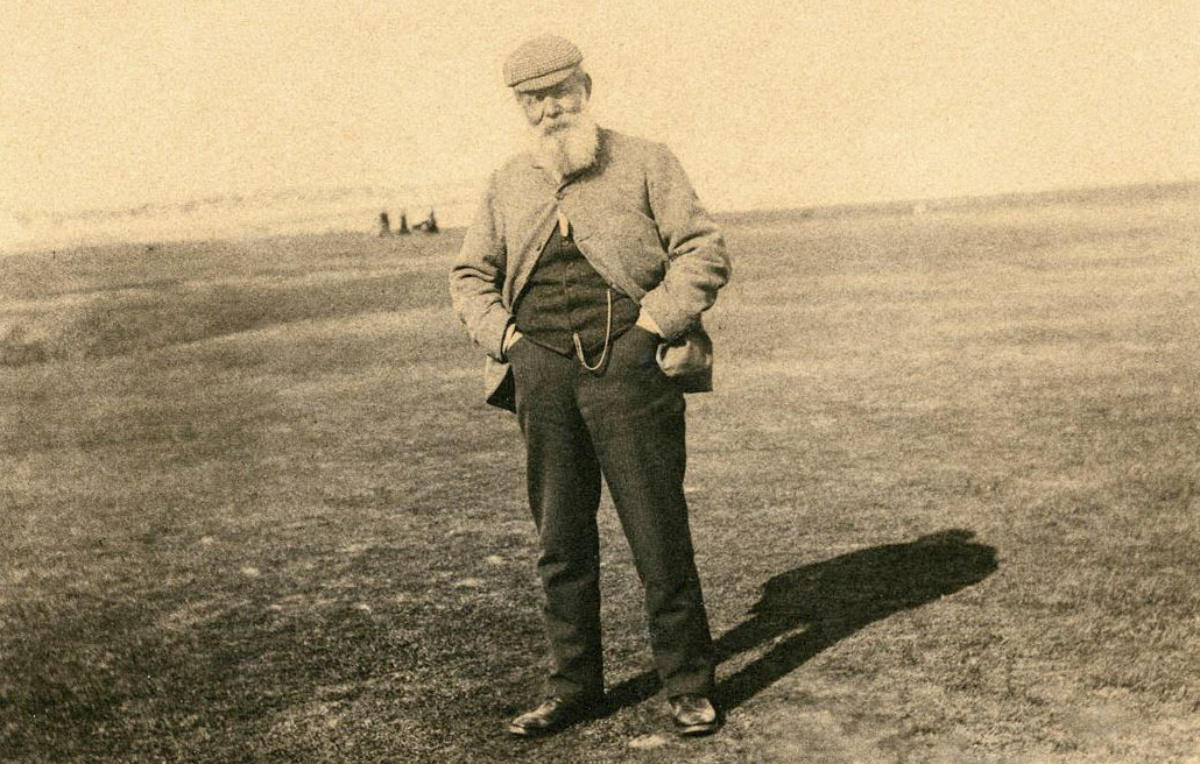

In 1901 the Daily Advertiser of Dundee reported that Old Tom Morris, aged 80, could be seen each day “enjoying a walk on the classic links and at the same time supervising with his keen eye the work of the green‑keepers, while on other occasions he can be observed wielding his club with youthful vigour.”

Tom’s life was defined by golf and in return no one would have a greater impact on how the sport is played. Likewise, he would redefine what it meant to be a greenkeeper, implementing methods that are still used today and which help fuel the multi‑billion‑pound industry of which today’s greenkeeper is a part.

For a number of years one St Andrews native revived the spirit of Old Tom, achieving worldwide fame in the process. David Joy starred in Titleist commercials alongside John Cleese, he graced magazine covers alongside Ian Poulter and he brought Tom to life for audiences all over the world. He also has a direct familial link, with his English grandfather being found a role as an official window cleaner for The R&A by Old Tom after the decline of the merchant navy visiting the town.

“Old Tom was the James Dean of his time,” said David from his artist’s studio, overlooking the town and the Forth of Tay. “He’d stand his ground, but in all my research I couldn’t find a bad word said about Old Tom, apart from being grumpy in later life. I would often say he was like Father Christmas in tweed.”

In 1821 St Andrews was in a poor state. Down to a population of just 1,800 people, the Reformation had seen the dismantling of the cathedral and in the 300 years since the town had not recovered from bankruptcy, » lying impoverished to the extent that an act of parliament sought to relocate the town’s historic university to Perth.

Hugh Lyon Playfair, the provost of St Andrews, began the clean‑up and issued 40 rules that every resident and visitor must adhere to. He also organised the construction of the first railway line to St Andrews, paid for on subscription by the residents. That, combined with new affordable ball technologies and the innovative activities of greenkeepers led by Tom Morris from 1863 onwards, would see St Andrews transform into the cradle of golf as we know it today.

Tom opened up the fairways, widening them to make the course easier for recreational golfers. He discovered the use of sand as topdressing, invented metal hole cups, used seaweed as fertiliser, introduced lawn mowers to the links and established 18 holes as the industry standard for golf courses.

He was also an adept course designer, lending his hand to some of the most admired courses in the world, such as Muirfield, Royal Portrush, Royal County Down, Carnoustie and Royal Dornoch. He famously charged just £1 a day plus travel expenses and would comfortably design nine‑hole courses if that was all the available land would allow.

“When Allan Robertson and Tom Morris ran their grand tournament in 1857 there were only 10 clubs in existence,” explained David. “When Tom retired, there was about 1,700 around Britain. He lives through the whole progression of the game and by the 1890s had designed about 90 courses himself. He used to walk along the beach and pick up the old sea gull feathers and use them as markers for where he thought should be a green or a tee. He’d then say ‘it’s up to you gentlemen, but this could possibly be the finest course ever conceived’.”

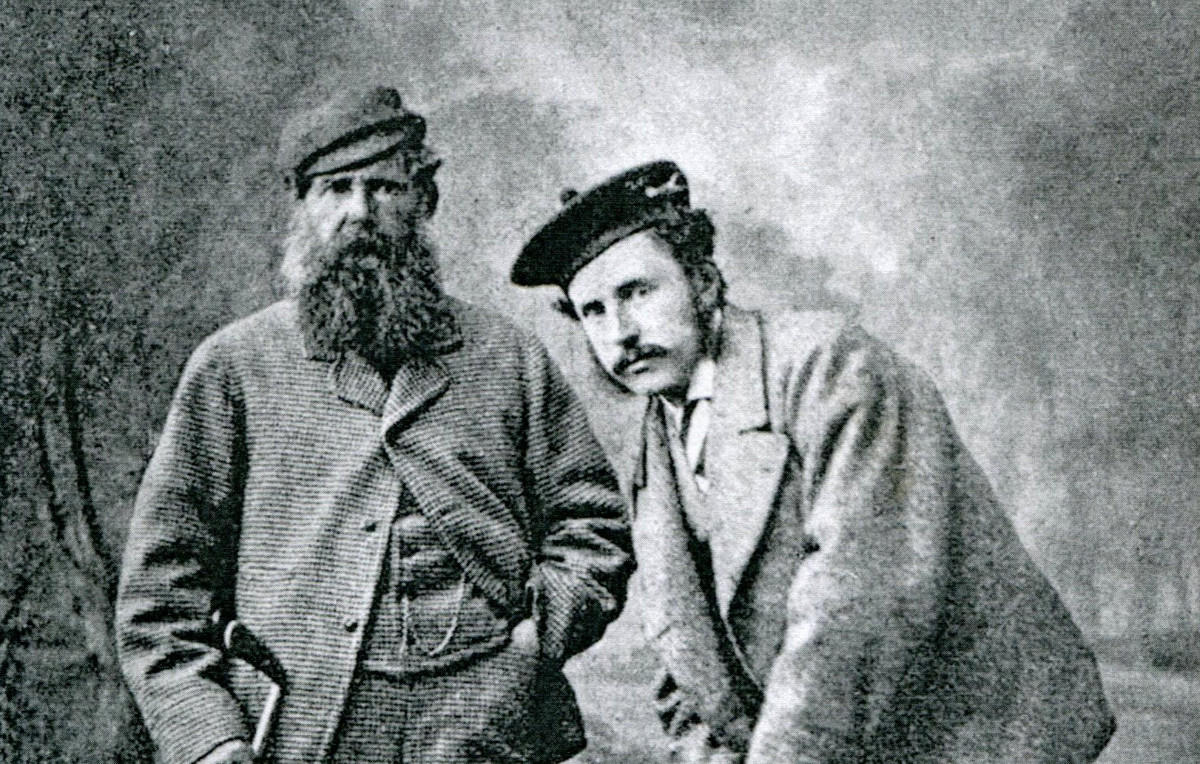

Allan Robertson is known as the first ever golf professional and had taken Tom under his wing as an apprentice in his golf ball making business when Tom was just 14 years of age. The two formed a successful business and unbeaten playing partnership until falling out over the advent of the new gutta ball, which was cheaper and more durable than Allan’s feather creations.

In 1851 Tom moved his wife and infant son to Prestwick to take up the position of ‘Keeper of the Greens’ and it is there that he accidentally, as the mythology surrounding the man states, invented the practice of topdressing. David explained: “Old Tom built his career around the cry of ‘mair sand’, but he’d actually discovered its impact on turf by accident. He was bringing a barrel of sand from the beach over to fix the Cardinal Bunker, when he spilt some by the 10th green.” With it impossible to pick up the sand, Tom spread it out and six weeks later noticed the grass in that area growing with increased vigour. When other areas of turf struggled he repeated the ‘accident’ and found that the results were replicated.

Despite achieving everlasting fame as a son of St Andrews, during the 1850s he was actually known as Prestwick Tom on account of his representing the club in many matches, particularly against Willie Park Jr of Musselburgh, winner of the first Open Championship. Following the 1859 death of Allan Robertson – the undisputed best golfer of his time who would die undefeated ‑ the members of Prestwick issued an open challenge to find the new world’s best golfer, and in 1860 The Open Championship was born.

In 1863 Tom Morris returned to St Andrews. He was given a salary of £50 per year, but that also constituted the entire budget for maintaining the links. In The Soul of St Andrews: The Life of Old Tom Morris, William Tulloch recounts: “His duties were explained to him: to keep the putting‑greens in good order, to repair when necessary, and to make the holes. For heavy work, carting, etc., he was allowed assistance at the rate of one man’s labour for two days of the week, and it was understood that he was to work under the Green Committee. Emblems of office were then handed over to him, to wit, a barrow, a spade and a shovel.”1

Tom’s return to St Andrews marked the beginning of the Old Course as we know it today. One of the first projects he completed was the construction of an access road to the sea for the lifeboat, known today as Granny Clark’s Wynd, while in 1865 the Swilcan Burn was banked and controlled, although the famous bridge had been present since at least the 1700s.

Tom also oversaw radical improvements in the maintenance of the course. Originally, players had putted and then were required to play their next tee shot from within a club’s length of the hole. Tom built separate teeing areas, allowing the improvement of greens surfaces. Originally the course had been cropped short by cattle but Tom encouraged the use of sheep as they were lighter underfoot. Greens were mown using hand scythes, “like a barber shaving a chin” explained David, but having seen the use of horse‑drawn lawn mowers in cricket and tennis, Tom introduced them to his golf course. This caught on and suddenly quicker and more efficient mowing practices made parkland golf on more fertile soil possible.

Tom catered to the poorer golfer, removing a large number of “whins”, the thorny impenetrable bushes that enabled weaker players a different approach to the green that didn’t require hitting over bunkers, while he also widened fairways.

J Gordon McPherson in Golf and Golfers (1891) compared the Old Course of 1890 to what it was like in the 1860s: “The course was narrow, the bunkers were yawning traps for topped balls, the whins were deadly snares for screwed or heeled gutties; now, one can slip along the side [of bunkers] without risking anything… The putting‑greens, too, are quite changed. Then, there was a variety of surface which brought out the greater skill; now, all are nicely turfed over and artificially dressed like billiard‑tables.”2

But Tom didn’t have it all his own way, whether due to the environment of the West Sands or the input of greens committees, who made their voice heard then as much as they do today. In 1891 Tom was instructed that his greenkeepers should dig up the bunkers properly and see that no grass is allowed to grow in them. That year he was also told to roll the greens more frequently than twice a year, as had been standard. Despite his reputation as the grandfather of greenkeeping and his standing as a four‑time Open champion, Tom wasn’t free from the interference of layman committees. Mr H W Hope of the Luffness Club is quoted as saying in 1895: “Old Tom Morris has often told me of the immense difficulty he has always had, and still has, at St Andrews, to get the greens committee to consent to the necessary work and regulations for keeping the course in order. I refer especially to the seeding, and the shifting of the play from one part of the ground to another… No green has… good chance of being kept in good order… unless they have a man like Tom Morris to organise, superintend and direct the work and who is ready to insist on the necessary work being carried out, however much the best of golfers may grumble at what is being done.”3

With an unrivalled knowledge of the links and his role as designer of the New Course in 1895, Tom was able to appease the greens committee who were left in no doubt that his actions had directly led to the town thriving as a golfing destination, whether visitors played or simply watched Tom play alongside Allan Robertson or his ill‑fated son Tommy, himself a four‑time Open champion but who would die in tragic circumstances on Christmas Day in 1875.

Yet even Tom’s love for the links wasn’t universal, and there’s actually a hole of which Tom is quoted as saying he wasn’t particularly fond. The High Hole is the Old Course’s 11th and despite being a par‑3, it’s among the trickiest in golf. In Tom’s day that wasn’t helped by the shifting sands of the Eden Estuary. Tom is quoted as saying: “[High Hole has] given me mair bother than a’ the rest o’ them put together. The hole was a great deal nearer the Eden in oor young day than it is noo; an’ the neighbourhood o’ the hole was aye changin’ an’ the hole itsel’ sometimes filled up after a heavy storm at sea.”4

The green would shift » and change and so Tom constructed a bank and planted turf behind the green to hold it in place and reduce drifting. In a world first, that would serve as a daily reminder to every golfer about the legacy of Tom Morris, he utilised a treacle tin on the High Hole as the original metal hole cup. Tom again: “I fell on that plan after a gude deal o’ study, an’ it suited to a tee. Then, when ither holes got raggit round the edges I had them dune up I’ the same way, an’ that was the beginnin’ o’ the modern style o’ the hole tin.”5

Although the death of his son hit Tom hard, he was a robust character, as evidenced by the fact he bathed each morning in the sea (three strokes out, four back). He kept himself hugely fit by walking the links each day and kept a window open in his house all through winter to ensure good air circulation.

In recognition of his service, he was made an honorary member of The R&A, but would rarely enter the clubhouse. “He was accessible to everybody,” explained David. “But when golf magazines and books started to be published from the 1890s onwards, he became a sporting legend in his time, the first one really, and was known as the grand old man of golf. But he knew his place and had an old‑fashioned respect for the gentlemen.” A century later and one of Tom’s professional descendants, Walter Woods, would decline membership of The R&A for the same reasons.

Tom Morris played an incredible role in the transformation of golf from an aristocratic pursuit to one that could be enjoyed by the general public. Despite personal tragedy, he acted selflessly in refusing to charge more than a nominal fee for his course design work and took great pains to ensure the game remained accessible to all. He also implemented countless techniques that greenkeepers continue to utilise today.

Speaking in character as Old Tom Morris at the conclusion of his documentary film Keeper of the Greens, David Joy recalls Tom’s attitude to the game, with a spirit that endures to this day: “Folk are far more interested in their own game these days, instead of appreciating the comradeship, the courses and what’s all around them. It may look as if my early days were a wee bit subservient but no, there was a mutual respect, a common ground, a sharing of this great game which has been my life.”

Looking for something to read next?

1. William Tulloch, The Soul of St Andrews: The Life of Old Tom Morris in The Golf Courses of Old Tom Morris by Robert Kroeger, pp26.

2. J Gordon McPherson, Golf and Golfers, in The Golf Courses of Old Tom Morris, pp xv

3. Peter M Crabtree, Tom Morris of St Andrews: The Colossus of Golf 1821-1908, pp205

4. Colossus of Golf, pp113

5. Ibid. pp113